Is Swahili a hard language to learn? Not with us!

April 19, 2022

Is Swahili a hard language to learn? This is always the first question new students ask, especially English speakers. This is a valid question because no one wants to spend money and time doing the “impossible.” By the end of this blog, this question will have been answered with reasons enough to relax and sign up for your first (or second) Swahili course.

Did you know that Swahili is a language spoken by more than 200 million people? It is primarily spoken in East Africa. Most of these people speak it as their first language.

Other Eastern and Central African countries also speak Swahili. So if you are planning to travel to Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo), or Mozambique it is advisable to learn the language.

Vocabulary

When learning Swahili one has to grasp everyday vocabulary for things such as greetings, introductions, and directions. Most speakers of English normally find it difficult because Swahili has almost completely different vocabulary compared to Spanish and English.

For example, Our tutors will tell you that despite this fact, some Kiswahili words are borrowed and “Swahilishized” by native Swahili speakers which in Swahili linguistics is referred to as “Kutohoa” (borrowing a word from another language and using Swahili rules to localize it). The word for computer, for example, is Kompyuta. The word for bicycle is baisikeli. In learning Swahili, you will find out that, unlike English which sometimes has words that end in a consonant, all Swahili words end in a vowel.

Reading

In the first lesson, you will learn how to pronounce Swahili words starting with the vowels “a e i o u” as well as consonant sounds.

Swahili has sounds that are not present in the English language. Consonant sounds such as /ny/, /ng/ as in nyumba (house), and ng’ombe (cow) respectively, have proved to be tricky at first for English learners, which is why they often ask if Swahili is a hard language to learn, but after a lesson or two with our Swahili tutors, students end up reading and pronouncing them correctly.

Once students grasp basic Swahili pronunciation, they realize that reading it is easy. Swahili is phonetic, meaning that it is read the way it is written (unlike English), thus simplifying practice for learners.

Once you grasp the basic rules and how to read we suggest that you find materials that are at your level and make reading a frequent thing. This kind of immersion will supplement what our tutors offer in class and help you internalize grammatical structures, learn new vocabulary, and understand how words are used in different settings and contexts.

Grammar

Swahili grammar can be tough for students who predominantly speak English as their first language. The sentence structure is vastly different in Swahili as compared to the English language.

The sentence, “What did she say?” becomes Alisemaje? In this case, the subject, verb, and question indicator je are all contained in one word. On the other hand, Swahili regularly uses about 8 nouns classes that a learner needs to get the hang of. Almost everything in a Swahili sentence has to agree with this noun class system.

Look at this example, Simu hii ni kubwa na ni nzito (This phone is big and heavy.) Hii (this), kubwa (big), and nzito (heavy) all agree with the noun, simu (phone). If you were to change the noun to mtoto (child), you would have to change the words above to agree with the noun because simu which is inanimate, and mtoto, who is animate, are not in the same noun class.

In linguistics, specifically second language acquisition, when grammar in L1 and L2 are structurally and functionally different, it takes a little bit longer and more exposure for learners to grasp it. A good tutor will expose you to literature, videos, and materials that will enable you to not only learn Swahili but also the beautiful Swahili culture in a fun and engaging way.

Written By

Kimathi

Kimathi got his education degree to teach Swahili at the University of Nairobi and taught Swahili language and literature at a high school there for three years before coming to the US for graduate studies. He has worked as a translator and editor for the last few years as well as teaching Swahili language and African cultural studies classes at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

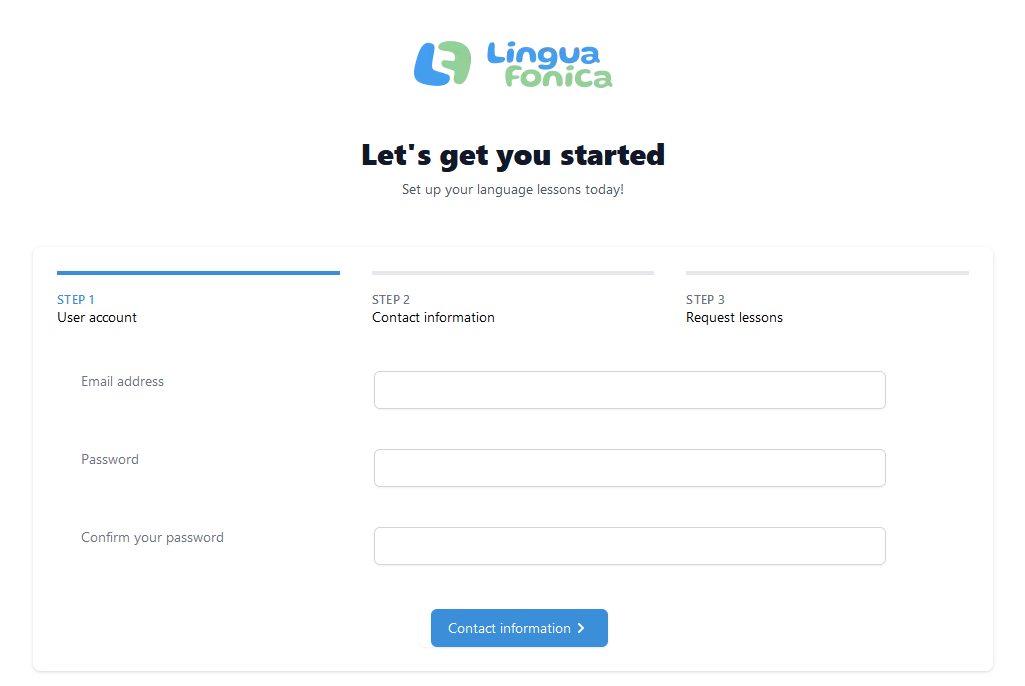

Ready to begin your journey?Schedule your first lesson now